Essays

Edward Hanfling - Catalogue Essay for 'See Visions and Dream Dreams'

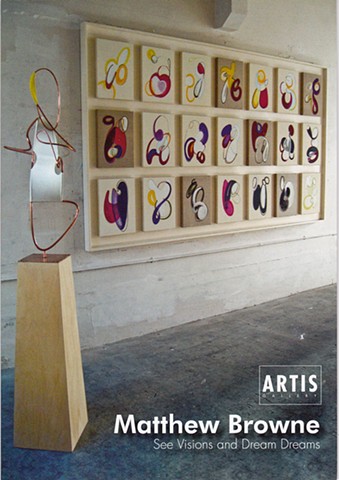

Artis Gallery - 29/06/ 2010 - 24/07/2010

In one’s experience of an artwork, is there a point at which a conclusion may reasonably be drawn? Matthew Browne seems to put his finger on a tension between how an artwork strikes us at first, as a whole, and the ongoing experience it offers (how it unfolds and changes as we look longer and think about it).

Ultimately, and at the risk of appearing to sum things up, I would suggest that Browne’s paintings and sculptures depend on time, and what happens in the viewer’s mind while they are looking, more than on an up-front, instantaneous impact. This is because they frankly reveal the means of their making, and the time that went into them. Obviously the viewer’s experience will differ from the artist’s, but because Browne has so candidly offered the residue of his experience, we are invited to dwell on our own, parallel re-creation of the work – or, perhaps, on our extension of the artist’s process.

Each painting in this exhibition appears self-contained. Browne’s ‘drawn’ lines and swathes of colour maintain a safe distance from the edges of the canvas. There is no danger that what is inside the painting will be confused with what is outside. You can see the painting as a whole, without distraction. And it gives an impression: of bulbous, curvilinear shapes, of overlapping planes, scalloped and transparent spaces, and even of a certain feeling associated with the specific colours relative to shapes, thicknesses of line, and surface textures.

All this can be grasped in an instant, without thinking about it. Yet, however much we might be tempted to judge the painting on the basis of this brief and potent moment, can we really claim to be seeing it ‘as a whole’? After all, we can glean more and more from an artwork by looking at it longer, and however long we look there is always more to be gleaned.

According to the critic Clement Greenberg, who is indelibly associated with Post-World War Two American abstraction (and Browne is ostensibly an abstract painter), that first moment with an artwork is what counts above all: ‘You see it as a whole without seeing any of its parts … the first way to see it is to see it as a whole.’ For the critic, this all-at-once experience is an experience of value; it is a judgement of the work: ‘Esthetic judging is spontaneous, involuntary, is at the mercy of its object as all intuition is; it doesn’t involve deliberation or reflection. … esthetic experience consists in intuited, not weighed, judgements of value.’

I do not think Greenberg was wrong, but I think we can add something to that all-at-once experience – and so, it appears, does Browne. He does not have a complete conception of a painting or sculpture before he begins: ‘I rarely know how things will turn out and it can be a tense game of hide and seek as cerebral sensations come and go, throwing the painting into a state of flux as the image is repeatedly pulled in and out of focus.’ The same applies to the sculptures: they are each the product of a succession of intuitive decisions – bending and twisting, adjusting, tightening, closing, ‘filling in’ and painting. Further, these intuitions become more tangible impulses and thoughts, which materialise as suggestive forms in the final image. And that is where ‘interpretation’ comes in.

When we look at one of Browne’s sculptures or paintings over a period of time – scanning the results of decisions made during the creative process – our thoughts may drift from matters intrinsic to the concept and tradition of ‘art’. Greenberg’s ‘esthetic’ experience, we must suppose, incorporates nothing but art as art; it is an extraordinarily intense exposure to the ‘art’ part of the ‘art-work’.

This is the extent to which we can separate ‘art’ from ‘life’; in Browne’s works, the former is analogous to the concentrated massing of pictorial form within the edges of the canvas, or, in the sculptures, the areas of space circumscribed or articulated by curves and coils of metal, sprouting from a neat plinth which in itself signals the difference between sculptural space and those uncontrolled realms beyond.

And yet, confining one’s experience of the work to its internal forms, one may nonetheless enter realms of thought and feeling that transcend those forms. The American literary critic, Stanley Fish, has pointed out that the reader of a text will often discard ideas and meanings picked up during the course of their reading that conflict with a retrospective summation of the text.4

As we prolong our experiences of Browne’s work, we should be open to whatever enters our minds, and not concern ourselves overmuch with whether our responses pertain to the cultivated realm of art as distinct from the stuff of everyday life. To use Fish’s words, ‘because it has been part of our experience, it means.5

1. Clement Greenberg.'The Bennington College Seminars' Night 2, 7 April 1971

Homemade Esthetics: Observations on Art and Taste, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. p. 99

2. Greengerg, p. 62. I have retained Greenberg's word 'esthetic', though it's meaning is the same as 'aesthetic'.

3. Matthew Browne, Artist's Statement, 'The Domino Effect'. April 2007.

4. Stanley Fish, Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities, Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England. Harvard University Press. 1980 p. 158.

5. Fish. p. 154