Features

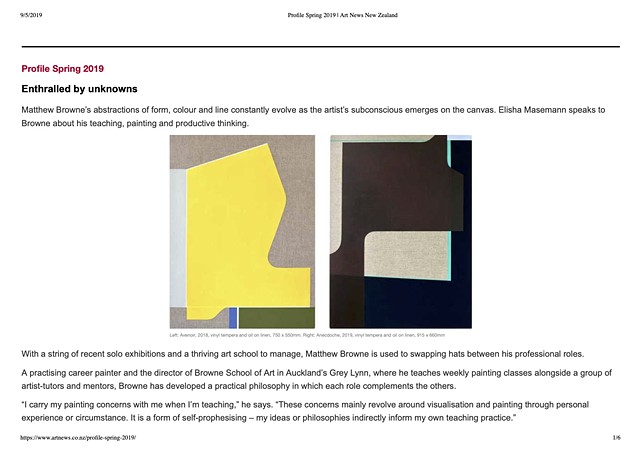

Matthew Browne’s abstractions of form, colour and line constantly evolve as the artist’s subconscious emerges on the canvas. Elisha Masemann speaks to Browne about his teaching, painting and productive thinking.

With a string of recent solo exhibitions and a thriving art school to manage, Matthew Browne is used to swapping hats between his professional roles.

A practising career painter and the director of Browne School of Art in Auckland’s Grey Lynn, where he teaches weekly painting classes alongside a group of artist-tutors and mentors, Browne has developed a practical philosophy in which each role complements the others.

“I carry my painting concerns with me when I’m teaching,” he says. “These concerns mainly revolve around visualisation and painting through personal experience or circumstance. It is a form of self-prophesising – my ideas or philosophies indirectly inform my own teaching practice.”

A multifaceted practice where art feeds into teaching appears to bridge generations in Browne’s family. His paternal grandmother, Ruth D Browne, was a distinguished New Zealand painter who encouraged him to set up an art school while still in his twenties. Browne’s mother, Jenny, recently retired from a successful career as a ceramicist, while his father, Michael, still an active painter in Wellington, was a senior lecturer in painting at prestigious art colleges in the United Kingdom from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Browne himself completed his Honours in Painting at Camberwell College of Arts in London in 1982. He began teaching courses on painting, colour theory and practice at Chelsea College of Arts, London, in 1988. After relocating to New Zealand in 1991, Browne continued teaching in the community and tertiary sectors. He completed a Master of Fine Arts at Elam in 1999, and had been painting and teaching in Auckland for nearly 20 years when an opportunity arose in 2013 to open an art school.

“It felt like the right time,” Browne says, “and a natural thing for me to do.” The school now occupies a number of large, well-lit studio spaces overlooking Great North Road, running term-long and year-long classes on drawing, painting, printmaking and art history.

Browne’s own time at art school has been influential for his painting practice in the last two decades. While attending Elam in the 1990s, the artist encountered Western psychoanalytical philosophy, in particular the theories of Carl Jung. While he admits Jung was “very unfashionable at the time” compared with Freud and Lacan, the Swiss psychoanalyst appealed to Browne. The Jungian philosophy of rationalising the human psyche into compartments that predetermine human personalities and experiences resonated with Browne’s vivid interest in people – the way they think, their differences. For example, he says, “It fascinates me that we can all have such personal, varied accounts of an openly shared experience. These are matters that I’ve been interested in for a very long time – the philosophy of thinking, of ideas, of difference. As a painter I try to turn these into visual, metaphorical images... It’s a way of trying to collate and make sense of it all.”

Painting for Browne is thus a medium by which images and sensations that reside in the unconscious mind are made visible. In this sense, his works bridge the void between the conceptual and material worlds, with each painting a physical expression or translation of subconscious thoughts. Browne relates to the writing of German art and perception theorist Rudolf Arnheim, who stated that “truly productive thinking... takes place in the realm of imagery”.

In Browne’s approach, that which was previously unknown or invisible becomes known and visible via the act of applying pigment to canvas. Each painted application responds to what was laid down before. The resulting abstract works are strong in their formal composition, but also have firm links to Browne’s conceptual process. “To make work with conviction,” he says, “I must have faith that the subconscious, associative ideas that underlie my painting will sustain a concentrated practice.”

“I’m in a position of being completely enthralled by the unknowingness of what I’m doing,” he goes on. This position seems to represent a maturity of practice, an at-homeness in the unknowns of painting, as Browne works towards a point of completion for each work.

Being actively ‘present’ through the act of painting and adopting a non-judgemental approach to mistakes allows shapes and forms to emerge organically. “Many of the paintings arrive through a process of constantly remedying my own errors. I find it quite interesting to view an error as a positive rather than a negative occurrence. I don’t necessarily know what’s going to occur in each painting or every step of the way – it just becomes a kind of conversation that I’m having directly with the forms within the painting.”

In seeking resolution through painting and discussing it afterwards, Browne says, “There’s a particular language that I feel comfortable with. It feels like it has a lot of openness to it. Although the works have become visually simpler, in many respects they’ve become much more complicated to discuss. Many of the things that are within each painting I frankly don’t know how to talk about. But there is a sense of truth and connection that I can feel, which can sometimes begin from something quite small.”

Browne’s most recent exhibition, Jouska, held at OREXART in April, explored the possibilities of how meaning is communicated and received: in particular, how one gives form to new thoughts, words or ideas. The exhibition title borrows from John Koenig’s Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, a web-based lexicon designed to “fill in the gaps in contemporary language”. The dictionary compiles newly invented words for strange social nuances and unique experiences. The word ‘jouska’, for example, is “a hypothetical dialogue played out in one’s mind”.

The paintings themselves are characterised by strong abstract shapes, decisive lines and bold colours. Flat bounded shapes are enclosed by precise curvilinear and straight-edged lines. Solid forms sit confidently on the surface in Ellipsism (2018); while in Ambedo (2018) they hover over lines or the exposed linen canvas. They jostle with one another, pulsing with energetic and emotive colour. Appearing variously stretched or squashed, the forms are individual, not generic, and speak to one another. Browne says they carry an ambiguity of meaning: irregular shapes are less resolved or bound, and therefore become more interesting and persuasive.

While in some works the natural linen is left exposed to lend breathing space, more often colour announces itself in rich hues and strong tones that reverberate off the surface. An energetic yellow in Avenoir (2018) is unavoidable in its centrality and scale, cheerful yet cerebral. Meanwhile the earthy greens in Vemödalen (2018) evoke visions of a natural landscape, without fixing that meaning. In Ellipsism , shades of teal and solid black are offset by an arching vivid red line.

Such coloured block lines play an active part on each canvas. Moving freely, they sometimes wander off-stage, from one edge of the canvas to the other. The lines serve a double purpose. On one hand, each contour offers a point of orientation, an anchor that other shapes push against. In Fitzcarraldo (2018), a tangerine line encloses a solid block, for example. On the other hand, a natural line may turn lyrically across a corner of the canvas, as in Ecstatic Shock (2018), giving a partial glimpse of a broader movement. The lines are thus active, not passive; they probe, and partly prop up shapes, while fixing others. This dynamic device – graceful, playful and vital, like a meandering thought – helps to contribute to the works’ multiple possible readings.

At this point the artist’s hand departs and the viewer’s perception arrives. Browne wants to draw his audiences in, for them to work to understand the paintings. He asks the viewer to delve further – consciously, willingly subscribing to the forms without being served a predetermined resolution. “As has been discussed for over a hundred years,” the artist says, “paintings are collections of shapes, colours and forms on a flat surface... but the viewer brings an enormous amount of expectation, which affects what a painting can actually achieve. A painting is a dormant object if there’s no ‘receiver’ for it. The work needs to be activated within the imagination – first by the person making it, and secondly by the viewer.”

Browne wants to continue exploring the translation of subconscious thought into abstractions of form, colour and line. He is working some way towards removing the presence of the hand altogether. “One of the things I try to do,” he says, “is to remove the directness of the hand in the work, so that it feels to me as though it’s come from an out-of-body experience. If my hand and brushwork is present, the physical body is made manifest. Without this trace, it is as though each work has effortlessly come from within.”

Back on the teaching front at Browne School of Art, the director and his colleagues are working towards end-of-year exhibitions in late November and early December for the year-long painting programme students. Enrolment for summer school courses will also get under way soon, so Browne will be wearing his business ‘hat’ once again as the school year marches on. Over time, he anticipates a gradual expansion of the teaching programme to offer more specialised courses.

In early August Browne’s painting Anecdoche (2019) won a Merit Award at the National Contemporary Art Awards, and will be on display at Waikato Museum until November. In this painting and the new works in production, the artist continues to work through his ideas on reception, projection and communication.

While incorporating multiple avenues of consideration, Browne’s practice has ultimately arrived at a mature style with which the artist is very comfortable. But it is also ever-evolving.

“Things will change,” he says. “How the work looks will change because painting is never static, it’s always moving forward. The forms I’m painting now were not what I had visualised three years ago – they’ve just slipped into that particular space.

“Right now, that space feels to me to be right.”